In honor of Women’s Equality Day, Soraya J. Kanakis submitted this article on women’s suffrage.

Thank you Soraya!

Women’s Equality Day: From then to Now

By Soraya J. Kanakis

Have you ever dreamed of doing something and been told that your dream is impossible? For me personally, when someone tells me that I cannot do something, I make it my mission to try even harder to succeed. I am following in the steps of my ancestors as are many women today who continue to fight for our rights. Recently, some rights have been taken away (Roe v. Wade), so it is important to know and understand the history of Women’s Equality Day.

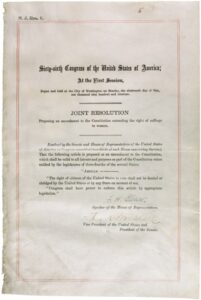

On August 26th, Women’s Equality Day is celebrated in the United States to commemorate the 1920 adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment (Amendment XIX) to the United States Constitution which prohibits the states and the federal government from denying the right to vote to citizens of the United States based on sex. It was first celebrated in 1971, designated by Congress in 1973, and is proclaimed each year by the United States President.

However, when the Founding Patriots gathered in Philadelphia for the Second Continental Congress to determine the future of the thirteen English colonies and their relationship with Great Britain and King George III, the representatives were not unified in their thoughts or proposed actions. Strong voices charged the English Parliament with the denial of the “rights of English citizens” and urged for separation. Calmer voices advocated a peaceful resolution of the conflict, even though mightily perplexed over the series of legislative acts that were designed to tax the colonists who were without a voice in the halls of Parliament. By July 1776, after a series of prolonged and often confrontational debates and votes, the delegates signed a Declaration of Independence, authored primarily by Virginia’s Thomas Jefferson, that advanced the call for separation with now resounding words, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

Why mention the Declaration of Independence when discussing the historic fight for women’s suffrage? In an examination of James Madison’s copious notes from the meetings, it is interesting to note the absence of any discussion regarding the role of women in the new society. Only in the letters between Boston’s John Adams and his wife, Abigail, do we find any mention of the “ladies”. Abigail Adams, an ardent student of the Enlightenment philosophers and no stranger to intellectual discussions among Boston’s political elite, reminded John to “Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favorable to them than [his] ancestors.” However, there would be no formal national platform advocating for the rights of women, especially the right to vote, until 72 years later in 1848 when women and some men will gather in Seneca Falls, New York to advance the idea. Interestingly, it will be another 72 years before women’s suffrage will become a reality (Mines, 2020).

The 19th Amendment guarantees American women the right to vote. Achieving this milestone required a lengthy and difficult struggle; victory took decades of agitation. Beginning in the mid-19th century, woman suffrage supporters lectured, wrote, marched, lobbied, and practiced civil disobedience to achieve what many Americans considered radical change. Between 1878, when the amendment was first introduced in Congress, and 1920, when it was ratified, champions of voting rights for women worked tirelessly, but their strategies varied. Some tried to pass suffrage acts in each state and 9 western states adopted woman suffrage legislation by 1912. Others questioned male-only voting laws in the courts. More public tactics included hunger strikes, parades, and silent vigils. Many of the supporters were sometimes physically abused, jailed, and heckled.

By 1916, most of the major suffrage organizations united behind the goal of a constitutional amendment. The political balance began to shift when New York adopted woman suffrage in 1917, and President Wilson changed his position to support an amendment in 1918. On May 21, 1919, the House of Representatives passed the amendment, and the Senate followed two weeks later. When Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify the amendment on August 18, 1920, the amendment was adopted. The face of the American electorate had changed forever while decades of struggle to include African Americans and other minority women in the promise of voting rights remained.

I find it interesting to think about why some women might have opposed giving all women the right to vote. Perhaps some thought that it might threaten the home. Passionate women in several locations which included Lexington, Massachusetts, who stood on opposing sides of the suffrage question. The Massachusetts association opposed to the further extension of suffrage to women organized in 1894 and spawned a Lexington chapter headed by Mrs. William Munroe. The founding of the Lexington Equal Suffrage Organization in 1900 prompted the formation of the opposing Lexington Anti-Suffrage Society at around the same time. It was led by Mrs. Frank C. Childs, Martha M. Harrington, and others.

A petition circulated in 1850 which asked the Commonwealth of Massachusetts to give women the right to vote and make them eligible to hold office, saying they should be “allowed a voice” in the imposition of taxes and the enactment of laws. Only six men agreed to sign, while nineteen women added their names including three members of the Robbins family and three of the Wellington sisters. The Robbins family included three generations of women in East Lexington who boldly advocated abolition and women’s rights between 1850 and 1900: Hannah S. Robbins, her daughters Julia Robbins Barrett and Ellen Robbins Stone, and Ellen’s daughter Ellen Adelia Stone. The anti-slavery movement proved to be a training ground for succeeding generations of women who believed that voting and property ownership were basic human rights.

For example, these women accomplish political change through other people. Anti-slavery petitions were one of the few avenues’ women had to express themselves politically in the mid 1800s as they could circulate and sign the petitions. At least ten anti-slavery petitions made the rounds in Lexington during the 1850s. Petitions contained two distinct columns: one for the signatures of “Legal Voters” (only men) and another for “other persons” (mostly women). Almost all these anti-slavery petitions were signed by women in the Robbins and Wellington families of East Lexington, often right at the top. On most petitions, there were more female signatures than male. Slavery was not abolished until passage of the 13th amendment in 1865. I cannot even imagine how demeaning it might have felt to have signed a petition as an “other person”.

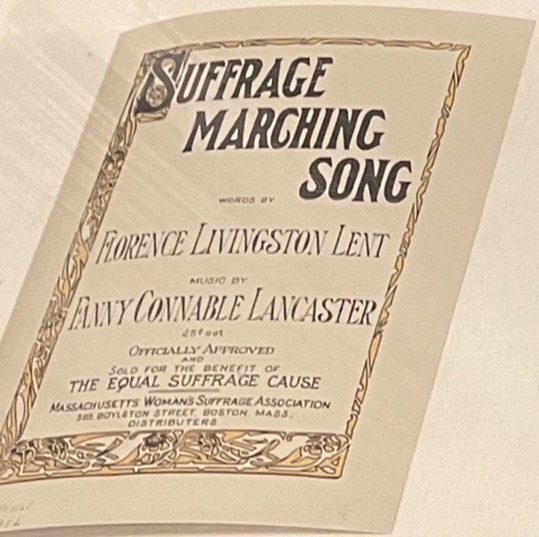

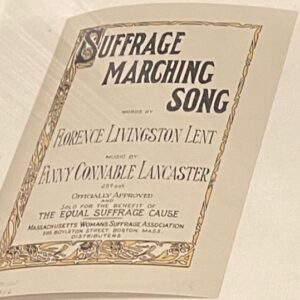

Massachusetts Woman’s Suffrage Association created a Suffrage Marching Song with words by Florence Livingston Lent and music by Fanny Connable Lancaster (Massachusetts State Archives). The use of music in the suffrage movement has three perspectives. The first is the music with lyrics, titles, and images that espouse women’s enfranchisement; next is the music performed at national suffrage conventions held by the National American Woman Suffrage Association; and third is the music that accompanied suffrage parades. This shows that even though the music used varied, the music that was played served an important role in unifying suffragists and underscored the goals of the movement. Some suffrage organizations published sheet music and the 1915 “Suffrage Marching Song,” with music by Fanny Connable Lancaster and words by Florence Livingston Lent, was published as a handwritten manuscript of the vocal melody. This particular song was sold by the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association “for the Benefit of the Equal Suffrage Cause” and included a page with the lyrics of “Battle Hymn of the Republic” and a pledge slip for volunteers asking, “What will you do to help Win Victory for Massachusetts in 1915?” The piece was available for twenty- five cents individually, $2.75 per dozen, and $20.00 per hundred (Lexington Historical Society). Unlike this handwritten manuscript, Gregori and Chapman’s 1911 “Women’s Political Union March” more closely resembles sheet music produced by professional publishing companies. This popular song sold for twenty-five cents and was available at the Women’s Political Union headquarters in New York City. The work was also published in arrangements for band and orchestra. Suffrage organizations, both national and local, advertised such songs in catalogs with other literature and consumer goods. For example, the NAWSA’s “Catalog and Price List of Woman Suffrage Literature and Supplies,” dating from around 1912, lists Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Suffrage Songs and Verses as well as two songs— “The New America” by Althea C. Briggs and “Equality” by Helena Bingham—ranging in price from one to twenty-eight cents per copy and sold by the dozen and the hundred, as well as individually (Catalog and Price List of Woman Suffrage Literature and Supplies; Brandes, 2016).

Appendix A. Lyrics of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, “Song for Equal Suffrage,” in Suffrage Songs and Verses, 1911, shown set to the tune of “Battle Hymn of the Republic”.

This song is also printed, without a tune, in Suffrage Songs: Selections from the Songs submitted for the Bishop Prize, February 1, 1909 ([Chicago]: 1909), National American Woman Suffrage Association records, 1839–1961, Box 74, Reel 54, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

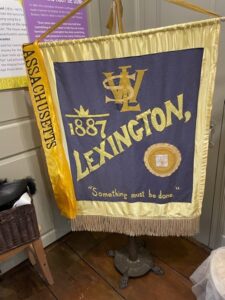

Appendix B. Women’s Suffrage League replica was made in 2020 by modern-day women’s rights activists and Lexington resident, Steigerwald.

In 1887 the Lexington Women’s Suffrage League made a banner to display at the Suffrage Bazaar in Boston, held in what is now the Orpheum Theater. It stated, “[e]ver since one of her boys was told that ‘something must be done’ in the face of a most formidable foe, Lexington has done something, and we shall persevere in our work, feeling sure that she will not fail us this time” (Louise Wellington Peaslee President, Lexington Women’s Suffrage League; Lexington Historical Society). The banner was frequently displayed at suffrage events in town and appeared at events in town. It was presented to a new coalition of activists who had formed the Lexington Equal Suffrage Association. This venerable banner appeared at events in 1913 and 1914 (Courtesy of Lexington Historical Society).

Appendix C. A rousing new Suffrage song.

Florence Livingston Lent (1873-1917), a Lexington woman, wrote the lyrics to a rousing new suffrage song sung by a marching chorus of 200 people at the suffrage parade in Boston. The music was written by another Massachusetts woman Fanny Constable Lancaster. The sheet music was sold for twenty-five cents a copy to raise money for the suffrage cause. Lent later took up selling “Suffrage Fund Coffee” to raise money for the Massachusetts Women’s Suffrage Association (Courtesy of Lexington Historical Society).

Appendix D. Joint Resolution

Appendix E. Women’s Equity Day

Appendix F. The Remonstrance against woman suffrage Boston October 1914

October 1914 issue of the quarterly publication by the Massachusetts Association Opposed to the Further Extension of Suffrage to Women (Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society).

https://www.primaryresearch.org/pr/dmdocuments/suf_mhs_remonstrance.pdf

Biographies

Biography Channel Mini-Video: Susan B. Anthony, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fIPtJpAQkmI

Biography Channel Mini-Video: Elizabeth Cady Stanton https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nCEaHGgUV-Q

Biography Channel Mini-Video: Sojourner Truth https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q-HfiryNoXY

References

Brandes, R. L. (2016). “Let us sing as we go”: The role of music in the United States suffrage movement (Order No. 10128749). Available from GenderWatch; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (1799283714). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/dissertations-theses/let-us-sing-as-we-go-role-music-united-states/docview/1799283714/se-2

Buckman Tavern, Lexington Historical Society, Lexington, MA

Mines, L. M. (2020). “The Hot, Humid, Historic Summer of 1920”. History Column, Chattanooga Times-Free Press, 09 August 2020.

NSDAR Educational Resources Committee “The Women’s Suffrage Movement: Visions and Voices” Contributor: Linda Moss Mines.

PrimaryResearch.org. The Remonstrance against woman suffrage. Boston. October 1914.

https://www.primaryresearch.org/pr/dmdocuments/suf_mhs_remonstrance.pdf (Accessed July 4, 2022).